Path 2: De Witt’s Catalogue

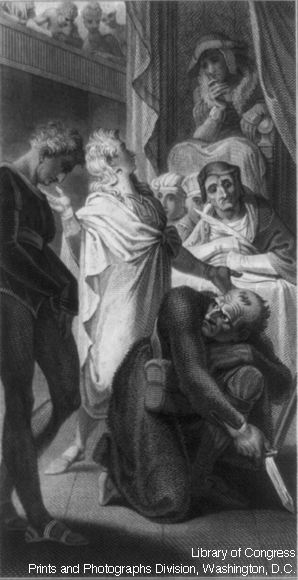

To develop a critique of melodrama and to encourage a self-reflexive practice of historical inquiry amongst my students, I want to return to melodrama when study the Black Arts Movement. To do this, I will share the story of my discovery of De Witt’s catalogue of “Ethiopian and Comic Drama,” along with the research that I am currently compiling, in order to unpack the abuses of melodramatic acting. Despite his curmudgeonly attitude and his dated study of the genre, Lacey provides a starting point for this critique. “Strictly speaking, “ he writes, “there are no characters in melodrama, there are only types, easily recognized and constantly recurring, such as the villain, the hero, the ‘persecuted innocent’ and the clown or ‘niais’. There are also, besides these four principles, two other prevailing types, the ‘accomplice’ and the faithful friend’” (20-1). From here, one need only look to the cast list of Pixérécourt’s Christopher Columbus in order to see the problem of these “types.” How did French actors play the “Savages” encountered by Columbus? What gestures and facial expressions did the acting manuals suggest for playing non-French roles? Along with the knowledge that melodrama was used to foster a nationalistic pride in the European countries where it emerged comes the knowledge that national identity relies on the formulation of the Other against which to cement its traits.

The popularity of the “Ethiopian” type in America during the eighteenth century attested to the racist ideology undergirding the American project of nation building. De Witt’s catalogue offers ample evidence that black people, though not exclusively, filled the subject position of Other to counter-balance the white male subject position engineered as dominant. There’s no need to rehearse the scholarship on this topic here, especially because I am by no means an expert on the topic, but I would like to share my findings on the “Ethiopian” type. I would also like to ask for assistance in compiling source material on the “Ethiopian” farce or sketch from those who are more active in this field of study. Or, if you have knowledge of melodrama acting manuals, I would love to learn more about that as well.

In “‘The Trouble Begins at Eight’: Mark Twain, the San Francisco Minstrels, and the Unsettling Legacy of Blackface Minstrelsy” (American Literary Realism vol. 41 No 3 (Spring 2009): 232-248), Sharon D. McCoy tells us that, “In the stage parlance of the day, ‘nigger,’ ‘Ethiopian,’ or even ‘negro’ (uncapitalized) referred not to actual African American performers but to white blackface performers. ‘Colored’ referred to African Americans” (240). John William Mahar offers similar information in Behind the burnt cork mask: early blackface minstrelsy and Antebellum and American Popular Culture (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999). Thus, the long list of play titles in De Witt’s catalogue refer to plays of the minstrel tradition, though not all of them featured blacked-up white performers exclusively. As Mahar states, “it is not clear how many of the characters actually appeared in blackface in any particular skit because the ‘Cast of Characters’ sections of the published Ethiopian sketches rarely indicate whether all the characters blacked up or only those with identifiable African American roles” (157). He points out that, “The sketches were also adaptable to various ethnic groups through slight changes in costuming or dialect,” meaning that these plays also mocked the French, Irish, and Dutch members of New York City’s populace.

Completely by accident, then, I have come across a list of plays that feature disparaging representations of black people and other members of the immigrant population in America paired with Jerrold’s text of Black-Eyed Susan. It seems reasonable to assume that the type characters created in the melodramatic form pioneered by Pixérécourt and then exported to Britain influenced the types portrayed in minstrel plays, and, therefore, that the melodrama form infiltrated the American imagination via racist depictions of the Other. By rehearsing this history with my students, I hope they will find a foothold in the work produced by the Black Arts Movement, which sought to destroy the image of black people created through this European theatrical tradition.

In recent years, when teaching works by black artists, I have discovered that students have little to no understanding of the history behind depictions such as Sambo or Aunt Jemima. Due to the structure of the theatre curriculum, students rarely take classes in Cultural Studies or American Studies where they might encounter materials like Marlon Riggs’s Ethnic Notions and a culturally-specific critique of aesthetic form. As such, teaching material from the Black Arts Movement and more contemporary artists such as Suzan-Lori Parks or Aishah Rahman has proven difficult. The fortuitous, though disturbing, discovery of De Witt’s catalogue has provided me with new material that might help to connect two seemingly distinct plays such as Baraka’s Dutchman and Pixérécourt’s Dog of Montargis, thereby strengthening the critical historiographical methodology I want to teach in my class.