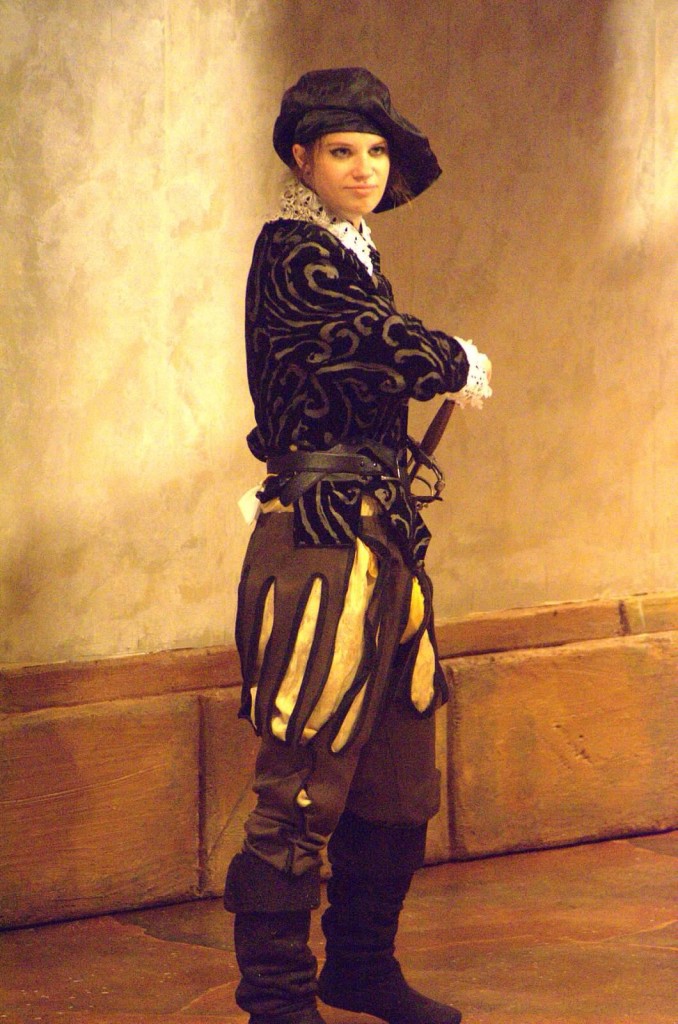

Hipolita and Luis changing, The Force of Habit,

Hipolita and Luis changing, The Force of Habit,

University of Puget Sound, 2015

If, as a theatre historian and director, you teach in a program where part of the department goals are to present a variety of shows that allow students and the community to experience theatre of diverse style, content, and form from a variety of historical periods (love that bulletin copy), there comes a time to plan to do a classical show. Inspired by a translation evaluation assignment I had been doing at University of Puget Sound with my first year seminars where we evaluated multiple English-language versions of a play from the Spanish Golden Age, I decided to direct a Spanish comedia in the fall of 2015.

This blog entry tells the tale of several pieces of scholarship that deeply impacted our show, in the spirit of demonstrating the richness theatre history and historiography incorporate into a show process. In our rehearsal, theatre scholarship was deeply influential not because we were aiming for a reconstruction of period practices, but because historical and literary critical scholarship gave us the vocabulary and imagery to name and develop many of our impulses and turn them into production decisions. I want to describe how those pieces of research shaped our blocking, character interpretation, and revision of the play’s ending

But first, I must admit that I don’t read or speak Spanish. My research language is French. Like the theatre generalist I am in my program, I primarily use Fuente Ovejuna and Life is a Dream when teaching literature from the Spanish Golden Age. I knew if I wanted to direct a Spanish play, however, I would need someone with the language to be my right hand collaborator. And, when I had a student in class emerging as a dramaturg who had the Spanish and excelled at doing that very translation evaluation assignment, I realized: this is my chance! Hannah Ferguson became my dramaturg and collaborator.

In our year-long arc of development, rehearsal, and performance, the four scholarly sources that most galvanized us were:

- “Marriage and Subversion in Comedia Endings: Problems in Art and Society” by Catherine Connor (Swietlicki) from Gender, Identity, and Representation in Spain’s Golden Age, edited by Anita K. Stoll and Dawn L. Smith (Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 2000).

- “The Power of Transformation in Guillén de Castro’s El caballero bobo (1595-1605) and La fuerza de la costumbre (1610-15): Translation and Performance” by Kathleen Jeffs from The Reinvention of Theatre in Sixteenth Century Europe, edited by T.F. Earle and Catharine Fouto (London: Modern Humanities Research Association and Maney Publishing, Legenda, 2015).

- “Gender Politics in Guillén de Castro’s La Fuerza de la Costumbre” by Kathleen Jeffs from On Wolves and Sheep: Exploring the Expression of Political Thought in Golden Age Spain, edited by Aaron M. Kahn (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011).

- “Lición de llevar chapines: Drag, Footwear, and Gender Performance in Guillén de Castro’s La fuerza de la costumbre” by Harry Vélez Quiñones, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 14:2 (2013): 186-200.

Already this list reveals that we chose to stage a relatively lesser-known play, The Force of Habit by Guillén de Castro, rather than one of the plays I had been working with in my seminars and theatre history classes. We didn’t start with Force of Habit. Hannah and I had begun by digging in to Life is a Dream. That seemed like where we were going to go, though we wondered where our mutual interest in gender was going to find its best match: in Lope de Vega’s wronged Laurencia from Fuente Ovejuna, or in Calderon’s disguised, honor-protecting Rosaura?

Then we met Kathleen Jeffs.

Kathleen is a dramaturg, scholar, translator, and director who teaches at Gonzaga University. She persuaded us of the queer potentials of the vastly underappreciated storehouse of Golden Age comedias and shared her translation of Force of Habit with us. Moreover, she encouraged us to take her workshop adaptation of the script apart, and gave us permission to cut it or rearrange it as suited our needs. Kathleen and Hannah and I agreed that we wanted to do a production alive to our struggles about gender and identity and that that might mean reworking the play.

Going outside the canon of well-known and frequently translated plays from the Golden Age meant that the scholarship we read was even more pointedly exciting: we didn’t have any baselines with this play. We had so much to discover. Kathleen shared with me that her perspective is deeply shaped by this source:

- Role-Play and the World as Stage in the Comedia by Jonathan Thacker (Liverpool, Liverpool UP, 2002).

Thacker introduced Kathleen to the play during her graduate work, and encouraged her to make her translation. His chapters titled “Patriarchy in Action: Guillèn de Catro’s La fuerza de la costumbre and the Distribution of Roles” and “Patriarchal Excess and the Emergence of the Desiring Self” represent the most authoritative scholarship we encountered in terms of detailing the way this play represents the gender politics of its period.

Overall, we found a spectrum of scholarship about Force of Habit, especially on the topic of the playful possibilities the play might allow in performing gender. Thacker represents one polarity that sees little evocation of liberation in the representation. Kathleen’s own scholarship rests in the middle point, suggesting that stage business makes this play much more complex in terms of gendered behavior. The work of my colleague Harry Veléz Quiñones, who is a Professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Puget Sound, sits at the other end of the continuum, explicitly queering the play in its analysis. I can’t adjudicate these different approaches as a scholar of the period, but as a director, it was very fertile to engage with the perspectives.

Force of Habit predates Castro’s best-known work, Las mocedades del Cid, the play that Corneille later adapted and which caused a furor at the French Academy. It follows the typical three-act comedia structure and smartly employs the character types typical to the form. It directly embodies the gender anxieties and pieties of its day, presenting a story about a brother and sister separated from each other in their infancy whose parents choose to raise the children dressed in the gender opposite to the sex each child was designated at birth. So, father Pedro, exiled from their hometown with baby Hipolita, raises her as a boy and transforms her into a solider so she might live with him more safely during his twenty years fighting battles in the Netherlands. Constanza, meanwhile, shut up in her father’s house, dresses baby Felix in women’s clothing and keeps him indoors like a woman to protect him from sword-fighting and honor culture duels, the things that killed her brother and caused her to be separated from Pedro.

The play begins when the family is reunited and Pedro declares that everyone can go back to their proper gender and they can resume life as a normal family. But it is soon clear that there is no going “back” for these young adult children because the reality there is to “resume” is the actuality of their lives as man-woman and woman-man. Felix and Hipolita experience their proper gender as aligning with the social habits and behaviors they were raised to present, not with the information provided by their secondary sex characteristics.

The play mixes comedy and seriousness as it tracks the collisions between Pedro’s demands and the new sense of self most of the characters must develop, but it emphasizes the comic. It is full of physical shtick about the difficulty of learning to use a sword or walk in high heels. It features budding romances. Conveniently, a brother and sister from a prominent family in town find Felix and Hipolita enchanting exactly because of their hybrid gender identities. A gracioso amps up practical jokes and intrigues. There’s also a set of double-crossings and duels that must be fought to preserve Felix and Hipolita’s honor.

It’s a high context premise played out in an over-laden plot, and, most complicated for us as contemporary artists, it seems to resolve in an uncomplicated way. By the final scene, everyone is clearly defined as a man OR a woman and the play ends with a firmly heterosexual marriage for both Felix and Hipolita. Though we were intrigued by the potential in performing this play, our very first challenges were to come to terms with that ending, or to shatter it. And here’s where the scholarship first supported us and freed us.

Pedro and Hipolita in their skirts,

Pedro and Hipolita in their skirts,

Luis, Octavio, and Marcelo in their gear

The question of genre and the question of the ending dominated our early conversations with Kathleen. One approach would be to reframe the comic business so that it showed and intensified the characters’ suffering with trying to master various technologies of gender, and to emphasize the tragic themes about identity and social oppression running beneath the surface of the play. This would be to focus primarily on showing the “patriarchy in action” as Thacker frames it. Thinking this way, Hannah described the play as a tragedy demonstrating of the awfulness of conversion therapy. That’s not where my heart was, however, and that became completely clear to me when I read Connor’s article on marriage and subversion in the ending of comedias.

Connor’s analysis of the meaning of conventional wedding scenes and her explication of “hard” and “soft” approaches to the narrative closure provided by weddings allowed me to articulate that I wanted to honor the combination of tragedy and comedy typical in comedias and have the final sequence be a marriage that doesn’t foreclose subversion. Connor voices the way that feminist criticism “seems uncomfortable with the presumed defeat of the formerly subversive heroine by the forces of the patriarchal order, tradition, and stability” represented by traditional wedding endings. She advocates accounting for the difference between the past and the present in both literary and material history rather than collapsing our understanding of Golden Age theatre directly into our own signifiers (23). She investigates how a female spectator in the Golden Age might have interpreted wedding endings of comedias and concludes that they would have reacted to them as representing variegated, compelling negotiations of complex social options.

Connor writes: “For the spectators of any culture, weddings are extremely important socio-cultural markers of change, transition, and new foundations in the lives of individuals and their immediate society” (25). Connor helped me name the way I see weddings (on stage and in life, in fact, I would describe my own wedding this way) as “symbolically central” and “essentially ambiguous” social rites of passage (27-29). Working with concepts of law and temporality as well as gender and drawing on documentation about married women’s work in the 17th century, Connor does a masterful job arguing that that weddings provide ending structures that are open even as they are closed. Rather than simply restoring order, Connor suggests wedding endings represent the creation of new orders still open to the indeterminacies in life and in art.

Using the idea of social rite of passage, it became my goal to stage a wedding at the end of Force of Habit that opened identity options even as it closed the narrative. Planning this production across the summer of 2015, as the United States Supreme Court handed down its decision removing federal barriers to same-sex marriage, I went to the costume designer with my developing plan. What if, I said, we ended with a big, queer wedding? What if everyone got to re-dress onstage, and ended up in gender mixed outfits? Felix could wear a skirt and doublet. Hipolita could have a veil and a codpiece and her sword (which she gives up, painfully, in Act I of the play). This wedding, like weddings in contemporary culture, could be about self-fashioning. About making a version of sex-gender-partnership with a beloved that suits that particular union: a narrative closure that is also an opening.

Soon we expanded the range. We aimed to out-As-You-Like-It As You Like It. I wanted the play to end with not just two weddings, but with four. We’d have Hipolita and Luis, Felix and Leonor, but also a marriage between Luis’s two best friends Marcelo and Otavio, and a marriage between Galvan, the clown, played by a woman in our production, and Ines, Leonor’s maid. Everyone would change clothes on stage, fashioning their preferred combination of male and female clothing. Then we pushed it to five couples because it became imperative that Pedro and Costanza be included. We established their official wedding in Act II—because their terrible shame, the reason for Pedro’s exile, is that they were only “secretly” married in their youth, and had been hiding their relationship and children.

Felix, Costanza, and Leonor in their “dresses”

Felix, Costanza, and Leonor in their “dresses”

Therefore, in our production, at the end, Pedro and Costanza also changed habits and wore both male and female clothing, at the request of their children. This plays against the text, which ends with Pedro declaring he is glad he returned everyone to their own nature. Instead, everyone was transformed our production, and we adjusted Pedro’s line to celebrate everyone “turning” to their own nature. That turning happened in different directions for different characters.

In short, we flipped the dynamics of Castro’s finale. Instead of the children transforming themselves because of the father’s demands and hardening the existing social order, the parents transformed themselves because of their children’s discoveries. Onstage, space opened for a renewed and transformed social order because the characters were able to change. Kathleen’s article on the “power of transformation” argues that comedias use language and create stage business that shows love transforming the characters confirmed and affirmed this interpretive pathway. Kathleen’s point about Leonor’s cruel enforcement of masculine heroics onto Felix starkly made us reconsider her character and pushed us to truly articulate the ways that each of the characters had to be understood as working both within and against the gender norms they had inherited.

Felix and Hipolita trading clothes

Felix and Hipolita trading clothes

As we chose to create a transformative wedding, replete with high-stakes character decisions and sexy connections, we also frankly acknowledged that the story we were telling exploded the temporal bounds of Castro’s work. We weren’t trying to indicate that the wedding we presented represented the historical reality of Golden Age Spain, though both Kathleen and Harry’s research provided us with examples of much more complicated public and private gender identity than official representation might allow. Because he is here, it was a great joy to that Harry could join us in rehearsal for a discussion of his article about the lesson of the chapines (the platform footwear women wore outside at the time). In his presentation, Harry shared knowledge about hidden histories of sexuality in the Golden Age, and told us, among other things, about the dildo collections of Spanish nuns.

This was somewhat how our research worked: we encountered the past in all sorts of strange and delightful specificity, but we also had to wrestle with the “official line” about gender and marriage from social tracts and dogma from the day that the most powerful characters in Force of Habit reiterate. Hannah, the dramaturg, was helping Kathleen on a soon to be published facing-pages Spanish/English version of Force of Habit during our pre-rehearsal research and during our rehearsal period. Because of that, she started working with a 17th century Spanish dictionary that she found quite marvelous in its strangeness and the way its entries relied as much on Catalan and Latin as they did on what she recognizes as Spanish. One of our favorite resonances from the dictionary was a definition of habit—a word we had been thinking of in terms of repeated behaviors, clothing, and Bourdieu’s notion of habitus—that linked the word to menstrual cycles.

Across our summer preparation, we developed our notion that in our production, we started telling a story set in 1610, but by the time we ended the story, we were in a place of conversation between the past and the present. I wrote in my program note about how we were having a “new-old” experience staging the play because of this conversation across time, and also because our process resembled doing new work (working from manuscript pages, revising and adjusting the script) at the same time it needed the techniques for staging classical plays (voice and text work for elevated language, dancing, sword fighting, working in a presentational word-driven style).

Our decision about time allowed the story to journey to the wedding at the end and the way we used dance mattered to that too. We added three dances to the action. First, we used a slow, period tarantella that Pedro and Costanza performed in a very formal fashion when they first saw each other again. The early phases of the play where we were more fully in the past moved in a more stylized way, slower, with deeper breath. For a medial moment, Marisela Flietes Lear created a solo for Hipolita to a spare flamenco beat known as the martinete. Hipolita danced this during her frustration with learning to walk in the chapines. The measured pace but intense energy of this dance and the way Hipolita rebelliously ripped off her costume’s sleeves and shoes during it helped index our temporal quickening. At the end, as a finale everyone danced a traditional sevillanas to a pop music version of the form by the contemporary band Las Ketchups called “Sevillanas Pink.”

Once we figured out how we wanted the end to work, we had to move backward through the script to set up how we got there. We wanted to create a subtextual relationship between Marcelo and Otavio, and were fascinated to hear from Kathleen and Harry about same-sex couples in the Golden Age. We needed to allow Felix and Hipolita to struggle with how they are asked to change their habits (literally and figuratively) and emerge as people acting with agency rather than leaving them as social ciphers.Kathleen had already edited her full English translation when she made the performance version we were working from. We made choices to streamline the action even further in Act II and III to reduce the double-crossing plot complications and allow Marcelo and Otavio’s roles more time to breathe.

As we built their relationship, we brought the final duel between Otavio and Felix onstage, instead of leaving it only narrated as it is in the original play. We created its storytelling arc as one that wasn’t only about Felix establishing his manhood, it was also about him using his own fluidity as he bested Otavio. The fight ended when Felix disarmed Otavio and then kissed him before reclaiming Leonor’s glove from him (our Felix grabbed Otavio’s hat then tore the glove out of the hat with his mouth and held it in his teeth, growling). Otavio fell to the ground when Felix took his hat and Marcelo rushed to him and, relieved he was unhurt, kissed Otavio as well. What was hidden was revealed.

Pedro meeting Felix for the first time,

Pedro meeting Felix for the first time,

while Felix is still in his “long skirts”

The duel kisses were one of several such moments of instability and revelation, including the moment when Hipoilta emerged in breeches for the wedding and Luis admired her codpiece. We aimed to be both serious and playful about gender, identity, and representation in our performance. We had performers with Latino and Asian-American backgrounds in the cast. We had cast members who prefer “they” pronouns to describe themselves. Our choice to cast a female performer to play Galvan also meant we asked whether or not the character was a man, or a woman, or, in one tradition for fools and soothsayers, both and neither. Hannah and I knew that our Galvan’s talent for physical comedy and rebellious antics meant that nothing she (the actor) was doing played by the class rules of Golden Age Spanish society, but we embraced the character (he/she/they) as an irruption of the carnivalesque in the space. The costume designer dressed her in a parti-colored skirt and breeches with codpiece that featured an embedded squeaky toy, which Galvan honked for emphasis whenever a prank went well.

These types of choices traded on the play’s investigation of interiority and exteriority, the relationship of social roles and inner self that Kathleen’s articles imagine into possibility. Our set designer, my colleague Kurt Walls, created set that referenced the architecture of corrales, but also added a curved ramp to the front of our stage that encouraged and allowed our direct interaction with the audience. Galvan was always talking to the audience and hiding on the ramp. This sense of projecting out into the audience space contributed to our decision to interpolate four speeches from Life is a Dream into the proceedings to give the main characters time and words to reflect on the monumental decisions facing them. Castro provides fewer of those moments in his text, though his great speech for Hipolita when she surrenders her sword is a heart breaker and her speech about needing to take revenge on Luis when she thinks he’s betrayed her won applause every night.

In Kathleen’s article about Force of Habit and El Caballero Bobo (The Foolish Young Gentleman), she notes the thematic and intertextual resonances between El Caballero Bobo and Life is a Dream. Some scholarship she cites suggests that Calderon knew of Castro’s play and borrowed details. Flipping that idea on its head, Hannah and I imagined what would happen if Castro’s characters got to read Calderon’s play. What parts would speak to their hearts? We also talked with Kathleen about the choice, and, as a collaborator, she challenged us to create more moments using blocking and business to increase Hipolita and Felix’s accessibility to the audience, and to see if, after exploring the text as written first, we still felt the need to add the interpolated text from Life is a Dream.

Heeding that prompt, we took a blocking suggestion from Kathleen’s other article very seriously. This article, about gender politics in Force of Habit, considers the interplay of words and staging extensively. Kathleen proposes that one effective way of foregrounding what’s at stake for Hipolita and Felix is to have them directly exchange as many of the clothes they are wearing as possible when they are first asked to change “back” into men’s clothing and women’s clothing in Act I. We went after Kathleen’s ideas about staging and stage business gusto. Our Felix and Hipolita indeed exchanged key pieces of clothing as they changed onstage in a moment of Brechtian gestus demonstrating what it takes to construct a man and construct a woman with clothes.

Then, following up on an important comparison Harry made, we maximized every bit of awkwardness and complication that we could about their complete failure to adapt to the new clothing or to attain the new skills they are supposed to master to be a good man or good woman. Harry’s brilliant article points up several things about how gender gets performed in Force of Habit, and one key insight is that Golden Age comedias abound with gender disguising/cross dressing, but that Force of Habit uses the convention differently. First, Felix and Hipolita are not disguising themselves in order to get something.

Second, in many comedias, when the main character disguises himself or herself, usually they are depicted as immediately being masterful at portraying the “other” gender. Seamlessly, they can sword fight, or dance, or walk like a lady, and they are convincing to others on this front. Felix and Hipolita, however, can’t do anything well except what they are used to doing; and the whole first and second act show the work it takes to get anywhere near being mediocre at new gender skills, especially the cursed walking in high platform shoes. These sequences must have made Force of Habit funny at its first performance, and it’s still wonderful and poignant stage business today.

Finally, Harry enumerates, typically once the character is disguised, he or she becomes overwhelmingly sexually attractive to other characters, so the woman disguised as a man gets pursued by other women relentlessly and vice versa for the man disguised as a woman. This type of set-up evokes and offloads homoeroticism and also suggests that gender fluidity has romantic potency in ways that are hard to pin down. On this front, Hipolita and Felix don’t so much fail as present a unique case study. Because they are not in disguise, the characters who fall in love with them have to be “open” in some ways about being attracted to them exactly because they are gender fluid. We found this to be very powerful in performance. “I never thought there could be anyone like her,” enthuses Luis in the script, and his status silences Marcelo and Otavio when they want to give him a bad time for his desire.

Working with Harry’s scholarship also opened for us the script’s implications about Pedro and Costanza’s youthful transgressions of gender norms and that was extremely generative for moments at both the beginning and the end of the play. In the opening scene of the play, Costanza tells Felix about his father and explains their hidden affair, noting how Pedro snuck into her room from the balcony. A scene later, when she meets Hipolita, who is dressed in men’s clothes, she reacts by describing Hipolita as a mirror image of herself at that age. For Costanza as a youth to look exactly like Hipolita at that moment would mean for Costanza to be dressed in male clothing as well. Harry’s close read of this moment helped us create a character biography about Costanza disguising herself in men’s clothes to sneak out of the house, and made us wonder about Pedro disguising himself as a woman to get in.

We were working imaginatively rather than historiographically at that point, of course, creating character biography in dialogue with Harry’s provocations (and one of the scholars he most directly takes on is Thacker). What was most important to telling our version of this story was that we were spurred to wonder about what other ways the parents too could be fluid and playful and desperate about gender, in ways that paralleled the younger generation. This made the moment we created when Pedro takes a skirt from Hipolita and puts it on before the play’s envoi speech feel very connected. In short, Harry’s scholarship helped us situate the play in a much sexier, more subcultural world than its surface text about gender might suggest.

Though I will stop here, there’s much more to consider about how we grappled with this text and what informed us. We produced the play in the midst of national and local discussions about the representation of transgender identities that impacted us, though our approach did not frame Hipolita or Felix as transgender in our current sense of the word. We also struggled with what the Golden Age emphasis on sexual purity and honor/shame mean in a time when college campuses are consistently thinking about rape and consent.

And, in a matter of performance technique, it was only when the student actors unlocked how to do the asides that the play truly began to work. That made me want to read more scholarship about asides as a matter of actor training, actor-audience relationship, and as indicators about historical shifts in the nature of dramatic storytelling and live performance. Perhaps that will be my next scholarly quest, when the calendar cycle turns and its time to do a classical play once again. In this process, the foundational and bold scholarship we read became utterly central to the performance experience we created.

Click here for Kathleen Jeffs’s entry on The Force of Habit on Out of the Wings, the Spanish-language play resource for English-speaking practitioners and researchers

{ 1 trackback }