I teach a unit on Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire that makes use of a variety of adaptations and modalities of the play, and that challenges students’ assumptions about the text with each successive lesson. Key learning objectives include identifying key themes within the play, analyzing characters across different portrayals, and comparing the textual with the visual. The brief descriptions below could be adapted into a variety of classroom activities, including pair-and-share, small group discussions, mind-mapping, student presentations, and so forth. I have incorporated several approaches with these topics.

I assign the play as part of a unit on Modernism, and the students first approach the written text within the context of course themes. For the purpose of this post, I will discuss how I teach the play within a course organized around “borders and margins.” For example, we discuss the way Blanche is marginalized by those around her as a result of her worsening mental illness and, ultimately, her trauma from being raped. We discuss the “borders” of gender and sexuality that are, by turns, both rigidly enforced and blurred.

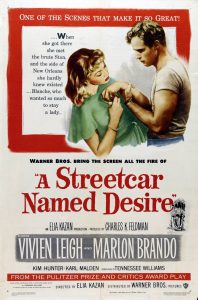

After our analysis of the play text, we turn to the 1951 film, starring Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh. These discussions afford students the opportunity to see how the film incorporates elements of both Expressionism and Realism while illuminating the themes of marginalization. Additionally, I direct students to observe any differences between the play and the film, which typically sparks a robust conversation about the film’s radically different conclusion between Stanley and Stella.

The third text brought to bear on this unit is the episode “A Streetcar Named Marge” from The Simpsons. This episode centers on a musical version of A Streetcar Named Desire (“Oh! Streetcar!”) which the town of Springfield’s community theater puts on, and in which Marge Simpsons stars. The episode finds emotional resonance in the parallels between Homer Simpson and Stanley Kowalski, and from Marge’s increasing marginalization in her own home. The episode also finds great humor in the adaptation of the play, with memorable songs and jokes about bowling. After a screening of this episode, I ask the students why they were laughing—what’s funny about this episode? I realize this seems to be an obvious question, and one that might engender flip responses ranging from “I don’t know” to “I actually didn’t think it was funny.” However, this question usually results in deep analysis on the part of the students to understand both the play itself and the nature of humor and parody.

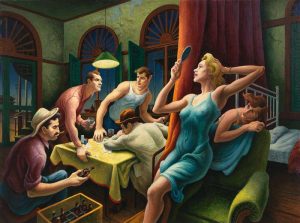

Finally, after the students have unpacked these various versions of the play, I present them with one final text: a painting by Thomas Hart Benton called Poker Night. Benton saw the original Broadway production of Streetcar and painted Poker Night as a tribute to the cast and production. It centers Blanche, as portrayed by Jessica Tandy, as she admires herself in a hand held mirror. Stella is seen in shadow behind Blanche, and the poker playing men are at the kitchen table. Mitch is staring, captivated by Blanche, while Stanley looks incredulously at Mitch.

I like to have the students first perform a basic visual analysis of the painting: what do you see? how is it lit? where is your eye drawn? etc. They discuss whether this painting seems to match the emotion of the poker night sequence, and if the characters are portrayed in way that matches up with previous analyses.

After discussing the painting on its own merits, I provide them with further context for the painting, which comes from letters exchanged between Williams and Tandy. Williams loved it so much that he wanted to recreate it as a photograph, to which the cast members agreed, except for Tandy. She refused because she disliked what she saw as Benton’s one-sided portrayal of Blanche. Williams assured Tandy she wouldn’t have to be photographed in such a sheer gown, but Tandy said that missed the point. She felt the painting portrayed Blanche as a victim—as solely the object of Stanley’s focus, and in her view, Blanche was too complex to be reduced to an object. (She also worried such a photo would lead playgoers to think the play was only about sex.) To his credit, Williams accepted Tandy’s reasoning, and canceled plans for the photo.

Students find this story interesting, because it offers them new ways to consider Blanche and how she relates to the rest of the characters. Students often point out that the one “error” the painting makes is that it puts Blanche squarely in the light, something the character takes great pains to avoid. Students also debate the portrayal of Stella in the painting; while she is at times overwhelmed by Blanche’s presence, should she really be seen as a cowering figure, behind her sister?

Bringing all these versions of A Streetcar Named Desire together affords students multiple opportunities to see how a dramatic text can be adapted, revised, reinvisioned, and even parodied. The benefit of a multimodal approach is that students who may be potentially disinterested in the play text itself will have several other chances to engage with the text in a way that might seem more interesting to them.

In closing, allow me to leave you with the advice of Blanche du Bois in “Oh! Streetcar!”: “A stranger’s just a friend you haven’t met!”

Resources

“A Streetcar Named Marge.” The Simpsons: The Complete Fourth Season, written by Jeff Martin, directed by Rich Moore, Fox, 1992.

A Streetcar Named Desire. Directed by Elia Kazan, performances by Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh, Warner Brothers, 1951.

Benton, Thomas Hart. Poker Night, 1948, tempera and oil on linen, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City. http://collection.whitney.org/object/4174

Devlin, Albert and Nancy Tischler, Editors. Selected Letters: Volume II, 1945-1957. New Directions, 2007.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

thank you!

{ 1 trackback }