Path 1: The Dog of Montargis

I entered Pixérécourt’s play with the help of three sources: Alexander Lacey’s Pixerécourt and the French Romantic Drama (Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1928), Louis James’s “Taking Melodrama Seriously: Theatre, and Nineteenth-Century Studies” (History Workshop no. 3 (Spring 1977): 151-158), and Marvin Carlson’s “The Golden Age of the Boulevard” (The Drama Review: TDR vol. 18 no. 1, Popular Entertainments (March 1974): 25-33). The Dog of Montargis seems to epitomize the genre with its transparent struggle between Aubri (the hero) and Macaire (the villain), its depiction of virtuous love in the amorous coupling of the mute Florio and the young Lucille, and its crew of type characters such as Blaise (the niais who provides local color) and, of course, Dragon, Aubri’s faithful canine friend without whom Macaire would surely get away with his vile deeds.

With that ensemble, the play may appear completely ridiculous for students. But wait! Before we pass judgment, we should watch the trailer for Stephen Spielberg’s War Horse (http://www.youtube.com/v/B7lf9HgFAwQ) and ponder how precisely melodrama has infused popular culture with its simple yet effective depiction of an ordered world in which everyone can tell right from wrong and good from evil.

Carlson tells us that the genre emerged from the feuds between Audinot and Nicolet on the Boulevard du Temple at the end of the eighteenth century when France was reeling from the Reign of Terror and preparing for the reign of Napoleon. While extremely popular, the melodrama had to compete against an eclectic assortment of entertainments, from tightrope walkers and dancing elephants to children drinking boiling oil and Daguerre’s diorama (Carlson 26. 30). To do so, it combined tableaux mouvant, musical leitmotif, horror-provoking scenarios of injustice, and stage spectacle such as erupting volcanoes and floods with high-grade pathos in order to tug at the hearts of its audiences.

Scholars cannot dispute the popularity of the genre, but they can belittle the means with which it attracted its audience. For me, Lacey’s vociferous dismissal of the “plebian” melodrama provides a great introduction to the detractors of melodrama: “[O]ne may say that the Revolution forced ‘le drame bourgeois’ to find refuge on the boulevards, there to surrender itself to a process of transfusion, as it were, but means of which it yielded up its life-blood to its more plebeian descendant, the melodrama” (19). His book charts the success of Pixérécourt as an innovative writer, entrepreneur, designer, and producer, but repeatedly paints the public for which Pixérécourt created his plays as downright stupid. On the topic of melodramatic violence, for example, he writes, “Physical conflict is, moreover, a means always ready to the hand of the dramatist, and especially the second-rate dramatist, by which he can create a sort of emotional response, particularly in the minds of the less cultured of spectators” (9). I found in these types of statements an opportunity to stop and reflect on the historical effects that may have produced this affinity for violence. I gave students a sheet of several comments by Lacey and asked them to first unpack the subtext of Lacey’s commentary and then to theorize why melodrama may have staged violence for its throngs of spectators. The students had little trouble realizing that after the French Revolution violence on stage would help audiences to process the violence in the streets.

To move beyond text to the embodied dimension of melodramatic acting, I turned to James who asks us to think through the contemporary manifestations of kitsch melodrama (think soap operas) back to the time before last-minute reprieves from death and the stock characters were made into conventions. James endeavors to take melodrama seriously, and he picks up that task by discussing the specificity of the melodramatic acting vocabulary:

Despair is not expressed as horror, pride is different from contempt. Moreover, the movements are dynamic. Gestures move through a spectrum of intensifying emotion; performers react to each other as if each produced a magnetic field. The whole has a rhythm—the music is of central importance—closer to ballet and opera than to modern acting: Dickens wrote that watching melodrama was like opera to a deaf observer. It flows towards significant tableau, it shatters a mood abruptly in a style closely related to the violent juxtaposition of feelings deliberately produced by Eisenstein with “montage.” (James 154)

Building on this description of the acting, I invited student to act the scene in The Dog of Montargis that contains this stage direction: “FLORIO answers by the most expressive pantomime that it is not gratitude but love, the most passionate, that he feels for LUCILLE.” It was, to say the least, difficult, but everyone laughed as the students failed to embody the enormous emotional weight of that stage direction.

I wanted to access the embodied dimension along with the historical context of melodrama in order to illustrate how the genre worked hard to fabricate affective belonging in its audiences. Charles Nodier, the nineteenth-century poet and critic, spells out this affective production in some detail in his introduction to Pixérécourt’s Théâtre Choisi:

What is certain is that in the circumstances in which it arose, melodrama was a necessity. The entire people had just enacted in the streets and on the public squares the greatest drama of all history. Everyone had been an actor in this bloody play, everyone either a soldier or a revolutionary or an outlaw….And make no mistake about it! Melodrama was not something to take lightly! It was the morality of the revolution! (cit. Pixérécourt: Four Melodramas, trans. and ed. Marvin Carlson and Daniel Gerould [New York: Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications, 2002] xv.)

He continues to praise Pixérécourt’s plays for diminishing crime on the streets of Paris and for imparting to its audience a spiritual clarity: “I say this because I have seen them, in the absence of religious worship, take the place of the silent pulpit, and bring, in an attractive form that never failed of its effect, serious and valuable lessons to the soul of the spectators” (xi-xii). Interestingly, even across the Channel in England where people suffered to rebuild after the onslaught of Napoleon, the melodrama, a French import, served the same purpose as a tool for nation building and spiritual repair.

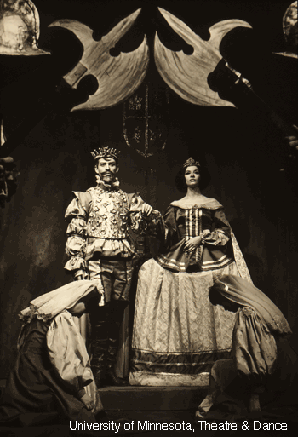

Having never encountered Pixérécourt’s work prior to this semester, I was intrigued by James’s challenge to take melodrama seriously. I presented selections from all these documents I’ve mentioned to my students and I asked them to take up that challenge with me. The result was a fascinating discussion of the migration of the melodramatic form from the days of Pixérécourt to our own. Interestingly, the University of Minnesota Show Boat has delved into the repertoire of nineteenth-century melodramas for its recent productions, and students were well aware of this. I’d like to end my tour of this path by sharing one of my student’s comments that was emailed to me after our class:

I was just thinking that the reason melodrama seems to stay relevant even today is because of the fact that it attempts to portray ordinary life in a more fantastical way. At a time when the real world has so much trouble and all fiction attempts to take people even further from the truth of their lives, melodrama tends to bring people back to reality in a way that other forms of entertainment don’t. This isn’t to say that melodrama portrays real life; it just shows the normal elements of the everyday in a much more exaggerated way. Since the first melodramatic play, I feel most popular theatre since has at least a little portion of melodrama in it, so we must acknowledge that melodrama, though not the best type of theatre, has a huge effect on how we view theatre today.

{ 0 comments }